Caterwauling Summertime Babies

June 6, 2014

It is, as some say on the Gulf Coast, “hotting up”. Not quite change your shirt twice a day hot, but already stay in the shade hot. Among other things hot weather is good for ripening tomatoes, iced coffee and arguments over small things. My college roommate and I have been arguing out the fine points of topics like Victorian adversaries for decades. Over time we’ve become familiar with one another’s tastes, beliefs and exaggerations. Not long ago, quite unexpectedly he proclaimed an affection for Julie Andrews, Broadway musicals, professionally trained voices and proscribed all else to the exile of “caterwauling”. Late in ones’ life I expect a certain amount religious retrenchment, dietary conversions, even divorces, but a Pauline conversion to musical theater surprised me. Broadway repertoire has charms, but deleting the astonishing range of 20th Century recordings we had shared for years set me wondering.

In my life I’ve enjoyed friends who could sing long selections of musicals a cappella, who were dogmatic collectors of recordings of chanteuses, and others who had framed “Playbills” on their walls. I admire obsession. I get it, at the same time I confess too much of my childhood was tortured by overexposure to “The Sound of Music”. Julie Andrews did nothing culpable: she remains Maria Rainer. Her soprano was lovely and expressive; whatever problems I have with the singing are mine. So I did find myself taking less exception to the canonization of Broadway, but more the loss of so much music to the lesser realm of caterwaul.

To my ear, the rigid tonal structures of western music, while pleasing, seem an artifact of a lost age I often appreciate as a tourist. It requires little from me but a credit card, suspension of disbelief and a cultural predisposition to sit still for three acts. That’s not derogatory; it’s in the nature of Western art forms. “The Sound of Music” is entertaining. It pits romance and the diatonic scale against Nazis and monastic vows. While reinterpreting history is one of the basic mythic devices of western theater, the more complex differentiation isn’t about historical melodrama and artistic interpretation, but between attractive and beautiful. Attractive has a broader range, or conversely beautiful has a deeper, narrower range. Both are noble human endeavors. What is easy or pretty draws us away from the unpleasantness of our lives; what is demanding and transformative takes us back to something that may be less pleasing, but more a more demanding useful truth.

I have lived in a fortuitously peculiar period. The sonic variety of our collective musical mind has been infected by recordings. People like me, born in the 1950s, have heard more different types of music than perhaps any other generation before us. We have heard it and responded to it, but been physically present for proportionally very few actual performances. Radios, records, CDs, tapes, television, movies, MTV, iPods, download and YouTube provide a constantly changing kaleidoscopic soundscape possessing both novelty and historical delicacy. As with most things, we know more than we have experienced. The Nazis came and went before I was born. Race, jazz, poverty and class struggle have remained part of the conversation of my lifetime; I’d like to consider “Summertime” from America’s first major opera “Porgy and Bess” and the notion of expressive caterwauling.

Like the performance of most operas, a performance of “Porgy and Bess remains precious. More people have seen Lady Gaga perform “Monster Ball” in its two years of touring than the combined audiences for every performance of “Porgy and Bess”. “Porgy and Bess” is another of America’s awkward masterpieces. It has an unaccountably erratic history of productions, enjoying limited runs in 1935, 1942, 1952 and notably 1976 as a revival by Houston Grand Opera. The 1959 film version was a production melodrama nearly more dramatic than the script. It too is assumed to be well known, but also seldom seen. The film was never given wide theatrical release and was shown only once on network television in 1967. Like many, I claim to having seen it and recall scenes and songs, including “Summertime”.

Most operas exist in the repertoire of storage. They are an antithesis of ‘popular’ music, to most people there are musical fragments or costumes that are almost recognizable. Mel Blanc may probably be the most recognized voice of the Valkyrie for the overwhelming majority of Americans. By nature opera is caricature; in America opera is an intellectual cartoon. It represents pure music with extensively trained performers and a demand for educated attention that is expensive in many ways audiences are not often willing to purchase. Nonetheless Americans assume operas will exist whether or not they like them, understand them, or attend their performances. As an opera George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” has struggled to find an audience identity outside of its composer’s roots in Tin Pan Alley, the Jazz Age and Broadway shows.

George Gershwin published his first hit song at seventeen. He had some classical piano lessons and positive experiences in that realm, but found his immediate future and fortune in popular music. He wrote Al Jolson’s black face signature “Sewanee” in 1917. He wrote songs for theatrical productions that were primarily musical reviews, song and dance, chorus, comics and hits. He understood his audience, the task of the song, and wrote to its commercial potential. The term “selling a song” came from this Tin Pan Alley period.

The piano industry reached its peak in the 1920s then declined with the Great Depression. Until the crash, pianos were the most common ‘must have’ item for every household, school and public business. Even today, a hundred years later, that prevalence of pianos remains part of our cultural memory. We aren’t surprised if a piano player appears in Western movie, in fact they’re cliché. Nor does it strain our imaginations when the Little Rascals rescue someone from piano practice to play football, when Mickey Rooney sits down to write the show to put on, or in the background music for tenement scene, dive bars, or cocktail parties comes as the trebly sound of a nearby piano player. We not surprised to find a piano anywhere. Legendarily in the 1920’s there were so many composers sitting at pianos picking out so many different songs at the same time on West 28th Street that it sounded like beating tin pans as opposed to music, Tin Pan Alley. Pianos and sheet music were a profitable industry, those without a trainable daughter or son purchased player pianos. Gershwin both wrote songs families could sing around a piano and arranged songs for piano rolls. He was extraordinarily successful at it.

Like all people of ambition he aspired to something more without the knowledge of what shape that would take. Like many from immigrant families, he recognized it would demand acculturation, invention and energy. He flourished with the jazz age, studied in Paris, and saw his “Rhapsody in Blue” and “An American in Paris” performed at Carnegie Hall. The music he composed for “Porgy and Bess” was in some aspects the culmination of his successes. It possessed sweeping themes and singable tunes. Gershwin’s seasonal “Summertime” was composed for “Porgy and Bess”.

“Summertime” was originally set to a poem by DuBose Heyward from the novel Porgy by Mr. Heyward.” “Porgy and Bess” was initially described by George Gershwin as a “folk opera”, that is, inspired by common songs and rhythms and interpreted in classical musical form. No different from works by Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Bartok, or Aaron Copeland all contemporaries of Gershwin. It’s generally assumed “Porgy and Bess” drew melodies from spirituals and other tunes Gershwin heard traveling in the South. In preparing the music he made an extended visit to a North Carolina barrier island. (There is an alternative interpretation asserting that “Summertime” is based on Yiddish and Ukrainian lullaby melodies.) The style of symphonic composing that was Gershwin’s forte was a style of musical interpretation and invention with a long history in Western classical music dating from Bach and certainly Beethoven. It was, as Ezra Pound wrote “…what the age demanded.” [Hugh Selywn Mauberley]. The age demanded overblown nationalistic symphonic music for growing radio audiences, American music sanitized from the jazz of the Jazz Age. Unquestionably the most popular and resonant song from Gershwin’s American opera was “Summertime”.

Many summers ago I was driving in Austin and a local disc jockey spent a silly and obsessive two hours playing nothing but different renditions of “Summertime”. I was fortunate to have escaped that easily; there are between 25,000 and 30,000 recorded versions. But I did came away wondering what “Summertime” could mean, even to me. Today Catfish Row is like the village Pagliacci’s wagon arrives in. The Harlem Renaissance is archived, along with Vachel Lindsey’s “Congo”, the St. James Infirmary and the Cotton Club. The roar of the twenties retains perhaps an academic allure, but in its moments it was quite the wild party. Stocks soared, religion was booming business, evolution was on trial, people seemed blissfully surrounded by a bubble of debt too big to burst, and sex, race, gangsters and music met for cocktails in glamorous lounges. It was summertime as the Depression arrived in its own wagon.

Here is the first recording of “Summertime” Abbie Mitchell sings and George Gershwin plays the piano and conducts:

http://youtu.be/x0g12TrSnIE

Why this version is heard so seldom surprises me. It’s gorgeous, and not just for 1935. It feels both human and ethereal. It seems to speak in an almost ambient religious tone. However this is not the version that Gershwin decided to finally employ. Perhaps it was too ethereal to attract investors, or not in the swing fashion. He continued re-working the setting as he worked on “Porgy and Bess” making adjustments, although he clearly was pleased with the basic “Summertime” as a piece and employed it three times in the opera.

The next oldest recording I could locate of “Summertime” was recorded in 1936 by Billie Holiday about seven months after the show opened in New York. http://http://youtu.be/9xpq1pLk-sA . There are echoes of tawdry jazz age colors in the introduction. Then Billie Holiday’s vocal moves the song from a lullaby into an ironic despair tinged view of life and the false oblivion of childhood. The insistent tom toms and Artie Shaw’s clarinet bring a kind of faux jungle decadence that speaks to both the Porgy story and the political oblivion of the times, simultaneously containing the guarded slumber of a child and the monsters of Jim Crow and worse. By comparison to the 1935 recording this isn’t as fully realized, but it possesses qualities of expression that allow the singer and song to engage. The band allows itself to become an shorthand of clichés and within the vocal I sense a hesitancy and inexperience, which lend to the recording’s the overall effect of singing to an infant amid jostling. If that was the intended effect or not, I can’t exactly determine. The band was between styles, the singer young, but already abused, and the recording hurried in order to take advantage of what publicity there was surrounding the opening of” Porgy and Bess”. It arrives more as an etude for something larger and later, which is how the song is initially employed in the opera.

Sidney Bechet recorded “Summertime” June 8, 1939 with Teddy Bunn on guitar. Summer is the character; there may be a baby and it may or may not be sleeping. Mr. Bechet’s interpretive soprano voices some sense of an alley between Montmartre and Basin Street as the afternoon’s heat is abating. Mr.Bunn’s blues-influenced guitar counterpoints the free musical extrapolation with a feeling of languor and restraint. Already the song has traveled some distance away from Gershwin into the hands of the interpreter, and Sidney Bechet was seldom shy about taking possession of a song. “Summertime” was well on its way home from the opera.

End of Part One

“…until day breaks and shadows fall…”

September 19, 2013

Quanha Parker

Somewhere between Waxahachie and Fort Worth driving west from my home in Houston to New Mexico I missed a turn and found myself with my map unfolded in my lap calculating the mileage of various legs of hypotenuses to return me to my intended route. I had time, so I wasn’t as distressed about being off schedule as I was at having to add hours to an already long driving day. Between the imprecision of my map and a few false turns on my part, I settled for a series of highway repairs on Rt. 380, if for nothing else, for the novelty. On 380 just west of Denton, Texas and a long hundred miles before Quanah, is a fenced open space with a metal sign fixed to the chain link that reads Muslim Cemetery. Not too far from the graveyard was a familiar roadside silhouette of a cowboy on one knee in prayer while his horse waits patiently. It’s not an uncommon sign, The Cowboy Church [www.cowboyfaith.org] has about 885 churches in the US and Canada. Not much farther I passed a large well-constructed Kingdom Hall that looked as if it used many of the architectural materials common to nearby stockyard auction rings. There are plenty of cattle and plenty of genuine cowboys in this part of the US. It’s a hard business built with long hours, tough weather, and plenty of labor. Animal husbandry is a Biblical occupation. The distance between many of the literal activities depicted in the Christian Bible or Koran is not metaphorical, only technological. There will still be blood, dust and lonely sky to contemplate as part of the day to day existence of many of these families. There were roadside signs for the Full Armor Biker Church, a “Commandments not Suggestions” billboard, I came to a rest area where two old boys had decorated their camper with hand lettered signs proclaiming why “Homos Go to Hell.” Dialing around on the radio I heard a man declare “My wife and I refuse to purchase any item that breaks God’s Heart.”

As I drove towards Quanah, Texas I kept wondering about the Muslim Cemetery.

There are approximately 125 Islamic mosques or religious centers in Texas and 425,000 members, the largest Muslim population of any state. 425,000 out of 26,000,000 doesn’t seem like much of a minority, but it’s still larger than the Native American population left in Texas (by contrast there are over 125,000 members in just the five largest Texas Christian mega-churches). In the Houston area there are nearly 50 Mosques and Islamic Centers, enough that they hardly draw attention. The greater Dallas Ft Worth area has about 20. The remaining mosques are spread throughout the state with about one in every city. Denton had a mosque. The growth of Islam in Texas remained a puzzle to me. In Texas instead of “What do you do?” you’re asked “Where do you go to church?” Perhaps those conversations don’t transpire the same way for everyone. But I wasn’t sure why any follower of Islam would be called to move to west Texas.

Buffalo Skulls

Buffalo Skulls

I was wandering through the southern boundary of the now non-existent Comanche nation towards a town named after Quanah Parker. The area where I first became lost wasn’t far from Fort Parker, a small blockhouse fortress built by in 1836 by a Predestination Baptist Community in what was considered “Comancheria”. That fort was the actual location of the infamous Cynthia Ann Parker kidnapping portrayed in John Ford’s, “The Searchers”. Her story inspired a film that remains both one of the best westerns ever produced, but also an intimate and epic consideration of American racism. Following her rescue, and subsequent return, she was famous throughout the Western World as the “White Squaw”. She was a Caucasian woman who chose to leave white society and return to live with the Comanche people. In racist symbology of the Victorian Post Civil War Era of respectable parlors, churches and taverns little could have been worse a worse crime against God, the white race, or culture. Ms. Parker’s plight was to choose the less cruel redemption.

To give the story mythic grandeur the film was shot on archetypal John Ford cinematic locations in Arizona and Utah. North Texas isn’t Monument Valley, Utah. It’s a peculiarly open claustrophobic landscape where it’s easy to get lost, even with a map. The geography rises from the piney Edwards plateau up through the hundred or so square counties in the high and rolling plains to the horizonless table of Llano Escondido. It’s hard dust hillsides, dry creeks, scrub oak, and hay fields that farther west give way to caliche, cholla, cotton and cattle feed lots. In summer its character is even harsher and even less inclined to generosity. This geography was once ruled on horseback by Comanche clans, legitimately feared since they had driven off the Spanish. The warfare between the Plains People and the US Army was a horrific culture of suffering on both sides. Take the worst images portrayed in stereotypical cowboy and Indian movie matinees, think of them re-envisioned in Quentin Tarantino’s nightmare and imagine them happening in 105 degrees, or in a relentless freezing wind.

Quanah, Cynthia Parker’s son with her husband, Peta Nocona, is famous as being the last Chief of the Comanche People. Legendarily he was wounded by Billy Dixon using a Sharpe’s rifle from a mile away (the distance varies based on the source) during the fighting at the Second Battle Adobe Walls. The Sharpe’s rifle was the weapon that allowed herds of buffalo to be exterminated at long distance without causing stampedes, and it is still possible to purchase a Billy Dixon model ($2,885.00). As a warrior Quanah Parker was a formidable tactician, a merciless fighter and was one of the last Native Americans to surrender in Red River War in 1875. He was also a participant in the inter-tribal Sun Dance of 1874 to restore the buffalo herds and the Plains People in the spiritual cycle of regeneration. Participation in a Sun Dance, along with numerous specified and unspecified Native American religious practices, was forbidden by Federal Law from 1830-1923, and was not de facto legal until the1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

The terms of peace following the Red River War forced Parker to live on the reservation formed by The Medicine Lodge Treaty.

That was one of the treaties that beginning with the Indian Removal Act of 1830, reduced the lands of the indigenous tribes of the Central Plains from an area roughly two thirds of the Louisiana Purchase (60,000 square miles) to designated portions of Oklahoma. The Red River War had been brought on by Manifest Destiny’s continual encroachment on traditional Indian territories and also by what is termed the great buffalo massacre of 1870. Buffalo Bill Cody earned his nom de guerre for purportedly killing 4,200 bison in eighteen months. Then he said he’d had enough (We all have limits.). Buffalo Bill’s departure notwithstanding in less than twenty years the vast herd of buffalo that ranged in the millions was slaughtered to near extinction for pleasure and to deprive the Plains Indians of food…or both.

Buffalo Hunters posing with Sharpe’s Rifles.

Increasingly since the Civil War the pacification of the Plains Indians” took the form of starvation and systematic destruction of resources. It was like Sherman’s March through a Sea of Grass (General Sherman was actually in charge, but the dirty work fell to Gen. “Bad Hand “MacKenzie). By destroying crucial portions of the symbiosis in a traditional nomadic route, the capacity of that lifestyle to remain viable is ended. Without open range, buffalo and horses the Plains People were doomed to a life they neither desired nor understood.

This statement by Paruasemena of the Numunuu Comanche, one of the signatories of both the treaties and the surrender following the Red River War like much of the literature of that genocide is romantic, brutally poetic, and true… psalmlike in its sensuality and lament.

“But there are things which you have said which I do not like. They were not sweet like sugar but bitter like gourds. You said that you wanted to put us upon reservation, to build our houses and make us medicine lodges. I do not want them. I was born on the prairie where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun. I was born where there were no enclosures …and where everything drew a free breath. I want to die there and not within walls. I know every stream and every wood between the Rio Grande and the Arkansas. I have hunted and lived over the country. I lived like my fathers before me, and like them, I lived happily.” October 21, 1867.

Shortly after the resettlement of Plains Tribes on reservations, the US Congress passed the Dawes act that effectively allowed the Federal Government to allocate parts of reservation lands to individual tribal members and sell the surplus to Euro-American settlers. This was one of many measures like Indian Schools, to help ‘civilize’ Native Americans into patriarchal nuclear families. The federal government in collusion with real estate investors planned and actively worked to use its power to force its new “citizens” to abide by the majority lifestyle and mores, and actively sought to suppress their practice of religious belief with armed intervention. They corruptly divided of tribal lands into private property and sold the rest. Quanah Parker is considered the last leader of the Comanche People because following the individual land allotments, the tribal life and culture that had flourished for generations was made practically impossible. Males were considered citizens and liable under Federal and Local laws, while suffrage didn’t come to Native Americans until 1924. In spite of this Parker became a successful cattleman. He hunted wolves with Teddy Roosevelt in an unsuccessful attempt to keep the government from selling more land from the Comanche Reservation, and built Star House that still stands today.

Beyond all that or because of it Quanah Parker became a religious figure.

Throughout his life Quanah Parker, not only refused to convert to Christianity or monogamy, he was one of the early proponents of organizing and protecting the rights of the Native American Church. There are currently approximately 250,000 members of the Native American Church. Quanah practiced his religion until his death in 1911. Native American Church observes rites that have been practiced on the North American continent for centuries. Some ceremonies also employ a sacramental use of peyote. Texas is the only State in the Union where peyote can be sold legally for religious purposes. Unfortunately the Native American occasionally makes news when some Anglo defendant claims he was in possession of various drugs as a religious sacrament. Ironically the sacred aspects of the religion have been appropriated and co-opted to such an extent that non Natives are discouraged from participating in most ceremonies.

I was also driving within a hundred miles of the Mount Carmel Compound of the Branch Davidians. Three members of the Texas Values group who demand the theory evolution be removed from science textbooks and replaced with biblical interpretation live and work relatively near. Texas was also home to Madalyn Murray O’Hair who founded the American Atheists. Continuing west towards Gaines County at the New Mexico Border several communities of Mennonites have resettled to escape the corrupting life in nearby Lott and other cities. Either unfortunately or by Divine guidance they’ve chosen a desolate area in a county adjacent to Clark County where a private nuclear waste dump has recently started disposing of radioactive materials from Los Alamos. I’m not sure which requires greater faith. If I wanted to find another semi-arid bit of geography where people had felt more empowered by God to act cruelly towards one another, I’d have to drive to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Placing the center of a compass on my location and extending the leg out 150 miles the circle it would inscribe would contain all of these religious activities and white clapboard churches on gravel roads, storefront ministries, and religious home schools with Internet curriculum. This could have been Dante’s dark forest and Quanah Parker could be my Virgil, I felt I was lost in sacred counties.

From the free range of the Comanche territory to finding a place to dump nuclear waste took considerably less than two hundred years. As a perennial passing stranger, I remain in awe at the variety of intricate systems of belief that hold us in our various places. For the most part I can only believe what I learned as a boy in my catechism classes, that I don’t know, or frequently I don’t possess the same answers as other people. Theology tries to be logical; religion demands to be hard.

There is a fundamental part in us that seems to desire to be connected with things ancient, difficult and mysteriously cosmic, and there needs to be some trial or sacrifice to achieve our worthiness to accept belief. That desire to have contact with something primal fuels many the behaviors we don’t understand in others. We need a parental approval far deeper than the school counselor imagined when she tried to explain why we were disrupting class. Regardless of how it manifests itself, if we don’t somehow believe we are in contact with a genuine touchstone to our past, we are as lost as an old newspaper ad. People share some need to suffer correctly, obedience is somehow wired into us beyond a behavior to merely survive. It is a path to salvation, just as hard as this state highway bending through the villages left outside the storm linked Gates of Eden. We traverse a series of speed zones built in townships where paradise has been postponed by a cruel variety of reasons and life continues amid the ungodly. Only here there are so many types of ungodliness buckling up with the pavement. When I stop for gas, it feels easy to believe.

A homing instinct for authenticity brings our bodies to places on this earth and allows us to endure and hope to understand. Perhaps it is in rare desolate places that religion seems most attractive. We’re misguided if we believe the people I’ve referred to are somehow primitive or inadequate because they don’t shop at Whole Foods, or employ the heels on cowboy boots for purposes other than style. Nor do I contend that they are privileged to a higher communion with the universe than an elderly widow living in a one bedroom apartment in Philadelphia. If a wrought iron man gets off of his horse to kneel and pray to the sense of order that keeps his allotment of land from spinning away from him whether by godless savages, or a government intent on persecuting his religion, or Stephen Hawking re-calculates the Higgs Boson’s relative value as a dark matter at the simultaneous beginning and end of the limits of our universe in the same frozen posture that has held him for decades, I may need both of those things and more to continue driving lost on this religious highway where theology has been written in blood down the way from the Dairy Queen.

E-Grace (part one)

September 11, 2013

E-grace

Bride of Frankenstein, Universal Pictures 1935

“Muster no monsters, I’ll meeken my own…” W. H. Auden

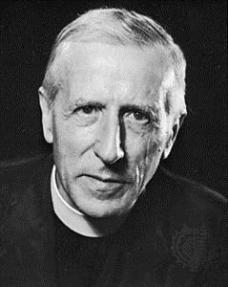

The day before Christmas a friend sent me an e-mail requesting me to blog about Teilhard de Chardin. I hadn‘t thought of de Chardin since I was an undergraduate forty years ago. Some of us may vaguely recognize a pop contemporary image of Pere de Chardin as the film character Father Merrin from The Exorcist series of films. [There is a more arcane and perhaps more rewarding intrigue linking Father de Chardin with papal demonic possession proposed by theologian/fiction writer Malachi Martin, but I’ll just allude to it and allow Amazon to profit from the passing curious. [Hostage to the Devil ].

A few actual philosophers have reflected a demi-existence as semi-fictionalized characters in film, mostly it’s a typecast for a harmless, hermit. A notable likeness of St. Jerome and also Martin Buber, I and Thou, befriends the Frankenstein monster in “Bride of Frankenstein” teaches it to speak, smoke and drink, then ironically is destroyed by his own recently civilized “friend”. A relationship only the tortured film genius’ of James Whale and Mel Brooks explored for filmgoers juxtaposed with variant images of the rough stitched Promethean that reaches beyond the limits of responsible science. Theirs is the warning in the first act that goes unheeded. Philosophers are generally characterized as hermetic, disengaged and often ridiculed. For most American audiences they are European contemplative residue, a curious wasted life. In Romantic literature were the early stereotypes for ‘mad scientists’, individuals who linger in places ‘men should not go’. Faust and Viktor Frankenstein are examples of these demonic scholars. Mary Shelly’s novel was published anonymously in 1818, and then publically fifteen years later, around the time of the Burk and Hare grave robbery/murder scandal, but fifty years before Darwin. The film “Bride of Frankenstein” was released in 1935, about the same time de Chardin was finishing The Phenomenon of Man, the same year Charlie Chaplin released his last wordless masterpiece “Modern Times” and Hitler became Fuehrer of Germany.

Monsters and comedians are one of the vocabularies we have for describing our subconscious thought to ourselves. Philosophers enjoy a posthumous regard, but generally as authors of aphorisms, i.e., “brainy quotes”. But we seldom think they are expressing what I’ve been feeling for a long time, more often they typify what I’d like to think if I could. They belong in old universities, movies, operas and novels, but even cable television can’t fill a late night rotation with “Top Ten Existentialist Diet & Exercise Programs“. Excepting actual philosophers, philosophy is a conscious activity, like a second language generally approached with uncertainty and a dictionary.

Marshall McLuhan famously portrayed himself in “Annie Hall” rescuing Woody Allen from a pompous bore on line at a movie. Coincidentally McLuhan’s theoretical global village was influenced by de Chardin’s writing particularly the concept of the noosphere. McLuhan was a devout Roman Catholic who initially read de Chardin from a hand distributed proscribed publication.

St. Jerome removing a Thorn from a Lion’s Paw

Niccolo Anton Colantonio, c.1445

Marshal McLuhan rescuing Woody Allen

Annie Hall, United Artists 1977

Martin Buber, Charles Darwin and Gene Hackman.

Although he didn’t die of a heart attack during an exorcism, Tielhard de Chardin’s actual biography is almost beyond believable cinema. He also belongs in the group of historical re-explorers like Highram Bingham and Howard Carter. His life was an awkward marvel of adventure, discipline, correspondence, and distance-made-personal as only someone from a religious order, in prison or having multiple affairs can compartmentalize life. He was a renowned paleontologist participating in the identification of both the forged Piltdown Man and the authentic Peking Man. He was a frequently denounced by the Church he loved, denied both Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur for any publication during his lifetime, but simultaneously a well regarded Roman Catholic theologian who was both heretical and obedient. His theological work was condemned, removed from shelves by some conservative clergy, yet surreptitiously published, translated and distributed throughout the world by others. Among those who privately promoted and simultaneously publically disparaged his ideas was one of the hidden hands that shaped Vatican II, an ambitious, but terribly un-photogenic, cleric named Ratzinger who went on to the papacy.

The fictional Father Merrin, the real Teilhard de Chardin, and the former Father Ratzinger.

It’s rare in the Twenty-First Century to discuss this heretic, mystic Jesuit. It’s rare since there are, to my knowledge, few Neo-de Chardinists who have translated his ‘transformative’ into something more profitable. The American Teilhard de Chardin Society is sponsored by the peripatetic Union Theological School, while its homepage is hosted at Yale. A membership costs $35 a year, $400 for a lifetime card. The society offers annual awards of $500 for the best research and $300 for the best lecture by a graduate student. No one has claimed either award for five years. For $15,000 one can purchase an original banned mimeograph of Le Phenomene Humain (by comparison a presentation copy of “Howl” recently sold for $75,000). In the tax-free world of religion this isn’t even walking around money. What neo-notion there is, is Progressive Theology which I assume still remains in the untroubled shallows of doctrine. His philosophical work dwells somewhere in the realms of Process Philosophers such as Alfred North Whitehead, Henri Bergson and Bertrand Russell, or in the tiny, exotic hothouse of Christian or Ecumenical Evolutionism. His notions of Omega Point theology may not be a heavy cross, but they’re certainly a complicated cross to bear.

Ostensibly, a request to produce a few hundred words on a philosopher wouldn’t be something I’m historically unfamiliar with, it was more like attending a college reunion. Writing other people’s papers was how I received my education in philosophy and writing fiction. de Chardin along with Hegel, Royce, Rahner, Sartre, Bonheoffer, and Martin Buber were worn tools of obfuscation and utilitarian quotation sources for my collegiate philosophy/theology ghost writing business. What topic can long endure a Hegelian Dialectic or an epistemological scrutiny? If Sartre or Buber wouldn’t provide a bon mote with pith, the cigar loving ethicist executed by Nazis could lend an unassailable, if sentimental, turn to even the most rambling essay. Where in the world of forced contemplation wouldn’t Bonheoffer’s term “cheap grace” be an undeniably summative critique?

Generally in writing philosophy papers my modified rhetorical form was to show a struggle, insert the apropos terminology with a modicum of awkward accuracy and then produce an epiphany. The more genuine task was to present that struggle, vocabulary and appropriate coming to understanding in a stylistic language that mimicked my customer’s classroom character and eradicated the existence of the actual author. That was a fair amount of sophistication for under $50, but my philosophical enterprise then (and now) was guided by a few cynical, but useful precepts:

- Writing about philosophy is portraiture for the unattractive; nearly every academic study desires flattery (and by extension the actual academic). In most institutions being an undergraduate professor is more like dulling office work than professing anything. For the most part papers are skimmed, then graded en masse by bored, disillusioned, frequently partially sober professors, who believe they should be doing something more important. For a ghost writer it’s crucial not to disturb that trance; ennui encourages self-deception. Although their professional vocation may be to see through illusion, they are nearly always willing to believe they’ve done a better job than they have, and students have done a worse job than they have. It’s more like a bad first date than an academic discipline.

- Philosophy starts with the premise whatever you think you know is wrong, and theology corrects what you thought you believed to be true. Philosophy is truth; theology is Truth.

- Common phenomenon in philosophical discourse are investing words with special single use meanings, violating syntax and inventing words, neologisms, portmanteau concoctions, triple-hyphenated-terms, retranslated etymologies and employing italics and parentheses needlessly. Philosophical writing displays the linguistic and grammatical ethics of an ambitious marketing executive. (Norman Denny, one of de Chardin’s translators, described using variant spelling of reflection [reflection and reflextion] to signify two totally different ideas as symbolic of the translator’s task.) One can pass sophomore Philosophy, by failing sixth grade English. Ghost writing success rests in employing as many tortured terms as closely together as possible and understanding the salvific potential of the word ostensibly as the first word in the sentence. No sentence can be too complicated or too dull.

- Modern philosophy, theology or religious philosophy are simpler subjects than historical philosophies since they only exist for specific realizations encrusted in self-described nonsense. In the philosophical, publish or perish world, garnering attention or selling a book is an understandably ambitious task. Imagine when writing about Sartre or Derrida, ect. you are talking to your drunken great uncle, as soon as you repeat what he’s said twice he’ll stop jabbering, otherwise he goes on until one of you passes out. Your task isn’t to debate; it’s to figure out what he wants to hear, rattle your ice cubes and agree.

- If you can’t grasp a philosophical text by a close reading of the preface, introduction, and index, the chances of understanding the main themes are slim regardless of the quality of stimulants involved.

- Any book or article you have been in the same room with goes into the bibliography. You did use them to reach that crucial point in your thinking. And at the end of the philosophical day who doesn’t find more direction from Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel than The Archaeology of Knowledge?

- Turn down all offers for short answer essays; you’re writing fiction not poetry.

In the years I wrote term papers the notion of plagiarism was a less negotiable standard of the Student Code of Ethics. My anonymity was the foundation of our bargain. Exposure of academic collaboration held strict penalties for my clients. Currently in our age of social networking, YouTube, apps, Moodle, blogosphere (there are Existential Web Rings among other unpredictable items http://www.webring.org ) and cooperative learning, my lack of identity and ability to finesse a personality struggling to a romantic enlightment on command would be considerably less valued.

Our Internet makes it possible for anyone to be near the information people need to know and a lot more they don’t. It’s an experiential flooding, not a teaching tool in the way libraries once were used to lead students to a particular truth. A library is a dedicated resource more like a labyrinth than a maze. It’s designed, like books themselves, for a kind of communal privacy, and like a book, it’s a self-contained, contemplative structure. Library collections are focused on preserving and reflecting the architecture of a civilized mind. A private library, like a private art collection, has always been a signal of cultural status and identity. On Beauty, a book length essay by bibliophile and philosopher, Umberto Eco, includes by way of examples of illustrations of beauty, the plan for the Medici Laurentian Library by Michelangelo. It was built over a cloister enclosed by graceful light passing through walls both protectively enclosing and expressing the spiritual and cultural value of books. We can appreciate its form as well as its contents.

The Internet library is an occasionally visible, floating machine that meanders after ghosts; relentless motion seems more important than contemplation. It resembles Borges infamous Library of Babel more than the Bodleian, Papal Lateran, or any research library. More than occasionally I use the Internet to augment my riddled memory. But usually when I wander around the Internet I’m not hoping for a specific answer, but rather an intellectual satiety akin to overeating. I become intoxicated with information. Some Internet engine records where I’ve wandered, it tracks my site visits, runs them through its incessant algorithms and begins to silently guide me where it constantly re-calculates I would be attracted to visit and to buy something.

Unlike the libraries I used growing up and where I occasionally did research for my term paper business, there are no shelves of selected volumes, no peer reviews, no periodicals assigned Roman numerals and consecutive numeration on a specialized topics, no reserves, no special collections, no perfume of aging leather, no soft spoken librarians to ask direction. In the Internet there is little direct moderation, only a staggering tide of information displayed ten items to a page, and an invisible code that follows every visitor…a mathematical creature like a mirror with a memory…a busy little shop clerk bringing items into your periphery. The noise to shush in this library is in your head.

Ironically apropos of these distinctions I began composing this without a reliable working Internet connection, or a library. Earlier I found a volume of de Chardin in a used bookstore (clean, no notes) and copied a skeletal chronology of him before a server somewhere collapsed. Between composing and contemplating I’ve squandered hours in the ritual of disconnecting, counting to twenty, and then reconnecting the modem. I received direction by invisible technicians from all over the ethnic world of dialects answering my telephone calls of complaint. I am now, as I was as an undergraduate, surrounded by a stack of a few opened books, some note cards, an erratic memory, insomnia and a willingness to revise whatever I write into something someone can have enough faith in to allow our common constructed epiphany.

Nothing brings me back to de Chardin like a common constructed epiphany.

End part one

Washing the Corpse

July 17, 2010

“and since they knew nothing about his life

they lied till they produced another one.”

Washing the Corpse, Rainer Maria Rilke

[translated by Edward Snow]

Tuesday my friend, Michael Silver Dragon died. He had been fighting his illnesses for as long as I knew him. He had been in hospice care for nearly a year. He was lifelong motorcycle rider; two summers ago he sold his motorcycle because he couldn’t ride anymore. A couple weeks ago he wanted to take me out for drive in his Tiburon. Over the last months he had taken up driving the mountain roads by himself and smoking little cigars while using his oxygen respirator. “I’m going to die soon” he told me” so cigar smoke isn’t going to kill me.” I suggested the exploding tank might; he laughed. It was a hacking laugh that suggested he was whacking things with a hatchet. I went on the condition that he wouldn’t smoke cigars while he was using oxygen. He took the curves and hills a little too fast, and drifted over the line a bit while telling me what once was down this dirt road, or what Fenton Lake looked like before the highway went through. We laughed a lot with the loud laughter you sometimes hear in bars—that vague coughing sound that usually has little to do with what’s been said, but is releasing something that isn’t being said, but wants to. The paved road ran out and we decided to turn back. He was tired, but wouldn’t let me drive. We stopped in Seven Springs and visited a friend. We sat in her kitchen drinking tea and listening to the brook that runs outside her back door. It was a painterly moment…maybe a little too restless to be Romantic or Impressionist.

A silence fell into our conversation as our friends ate lunch. I looked at Michael and saw suppressed surprise in his eyes. He was lost, but I didn’t know where I should look to find him. Eventually the tea and honey found him and brought him back. Like most return trips we don’t remember many details, that was true of us and soon we were saying good-bye in the library parking lot where we left my car. By chance his wife and friend, Berta, was parking her car to attend a meeting. We all stood hugging and thankful. It would have been a kind perfection for things to have just evaporated into those instants of affection and fullfillment.

But they didn’t.

That is the kind of vignette that makes genuine human character rhetorical. It’s warm, sentimental and allows itself to be contrived by the pathos and a hinted knowledge of death. At this point Michael Silver Dragon is really dead. But in these scenes I have replaced him with my desire to produce an elegiac fictional Silver Dragon. I’m not writing an obituary; rather contriving a sweet eulogy intended to make my reader abstrusely sad, but also to engage in my fictionalization as a form of easy belief. You as my reader must believe this, in order for it to grow to be the truth. I confess to knowing practically nothing factual about Michael. For me he had little history other than our private shared adventures on my holidays and vacations. He could have been my Great Uncle Johnny. The day after he died I was asked to write the obituary. Those dictated facts were a series of revelations, which I suppose a certain amount any obituary actually is, but an obituary is also a symbolic punctuation indicating when the dead receive a new life as adjuncts to those of us who remain and construct memories. They belong to us, like movie characters or pop stars. We build the dead out of need. We shape them as the poetic corpse washers shape the lies they need to tell one another. This is more about me, about my need to remember and forget the same thing.

“Not all truth comes in beautiful words; not all beautiful words are truth.”

Last Saturday morning Berta called from her panic. Michael wouldn’t wake up. Again. He had died several times in the years I’d known him. Yet he returned from the hospital again and again. He had fallen and hurt his neck, he had pneumonia and he didn’t want to eat. When I arrived I found him twisted awkwardly on his bed. Berta was trying to support his neck. He moaned and pulled at bed clothes and the neck support pillow until his head drooped forward in a posture that made me cringe. Together we lifted and shifted him in their bed. He made noises, but not to us. Then he fell back to heavy sleep. Berta had hospice on the telephone. They were suggesting a hospital bed and neck brace. They were willing to bring them out that afternoon.

Things were collapsing too quickly.

Berta and Michael had scheduled respite care in a facility in Albuquerque so she could go to her father’s birthday party. I was supposed to spring Michael from the rest home the following Saturday. We would eat dim sum, find some mischief, then I’d bring him home. Berta and I surveyed the available space in their home. It would take some significant rearranging, but we could squeeze a hospital bed in somewhere, shifting out her study and furniture .

Things were spinning apart.

We tried giving Michael his medications. It took two of us to try to open his mouth. The pills drooled out on the wild goatee he’d been growing for twenty-five centuries. He was thrashing weakly. He was moaning. The medication took effect, he seemed quiet. I drove 30 miles to the Walgreens in Bernalillo for a foam cervical brace. We got it on him. The collar didn’t provide him any comfort. The hospital bed didn’t seem such a good idea. There were no beds available at the hospice hospital unit.

We’d have to wait for someone to die.

The next morning Berta called. A hospice bed on the unit was available. Michael would be transported by ambulance to Albuquerque. It would take most of the day to transport him and get his paperwork checked at the hospital. She wanted to do it by herself. She said she done it so many times, that alone was better. She suggested I come

later in the afternoon.

I drove to Santa Fe to the International Folk Arts Festival for diversion. I wanted to get lost in the crowds and ersatz open market of rugs, jewelry and carvings for a couple of hours. I had a couple of artists I wanted to see specifically. One made fantastic painted resin dioramas of Bolivian peasant life crossing barriers into other realms where they might be suddenly drinking or dancing with devils, angels or skeletons. The other was a Mexican muertos artist from D.F., who carved intricate calaveras on matchsticks. It was the last day of the festival; many of the artists were tired of listening to English. They sat sullenly painting, or dully detailing metalwork with small hammers. I couldn’t find the two artists I wanted to see. By chance I ran into Jacobo Angeles, a wood carver whose studio I had visited in Oaxaca. He was exhausted from shaking too many hands. His English met my Spanish and he turned me over to his nephew. “We have a website.” He handed me a card angeles@tilcajete.org. I bought a glass of iced tea made with all renewable resources. It had rooibos leaves, beet roots and ginger; I had a stomach ache, albeit a healthful one. It served to keep me from being dulled by the early afternoon sun. There was drumming and dragon dancers were leaping on the plaza as I boarded the bus to the parking lot.

Driving back I found the World Cup final on the radio. It was being broadcast on a Spanish station. With the score zero, zero and cinque minutos left in regular time I spotted my favorite used bookstore in Santa Fe and a place to park. I found a used CD of the master copy of “John Coltrane at the Village Vanguard” and Edward Snow’s translation of Rilke, A Head of All Parting. These items seemed essential in my immediate future. When I returned to World Cup the game was in extra overtime. Although I, along with the entire Spanish speaking Western Hemisphere, had waited for the elongated scream of “G-o-o-o-o-a-l!” when it happened I wasn’t much relieved. I stopped at the Santa Domingo reservation for gas. $2.59 a gallon. I chewed a few berry flavored Tums and drove towards the hospice hospital in Albuquerque.

Berta called on my cell phone, room #1029.

In Lovelace Hospital if you press the elevator button for the tenth floor any employee on the elevator, or getting on later, first is suddenly silent, tries to smile, then looks blankly away. Modern hospice care is a hospital service, not a dread Hotel Dieu, but quiet, orderly and intensely humane. What judgments the staff makes, they keep to themselves. They don’t use euphemisms; it’s death and dying. They look at you when speaking with you. When I asked at the desk, they knew who Michael was and that Berta was in the room with him.

Michael looked worse than the day before.

He was restless and more jaundiced,

He appeared to be suffering less.

We had had our last conversation.

I smoothed his hair and sat down.

Berta was exhausted and dazed.

We went out to find some dinner,

it turned out to be salads we pushed

with our plastic forks and then threw away.

She drove back home and I returned to #1029.

I sat as the sun was starting its slow summer setting. The hide-a-bed love seat sunk me deeper than was comfortable, but there was nowhere else to go. As distraction I wondered about Walt Whitman’s days as a nurse. How he must have learned, as these nurses had, how to intimately diagnose each detail of approaching death. I wondered how he was able to keep experiencing the buzz and yarp of the world. I wondered what that change meant to him as he walked home, or worried about enduring his persecutions and keeping his position a little longer. Did he still see the great cosmic body transcendent…or like me in this golden evening, seeing it struggling minute by minute, breath by breath, cell by cell, system by system, moving towards absence.

Four years ago Michael completed translating The Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu. Having no Chinese, only his ambition translated the notion of wei wu wei.

At the party when he finished it, I imagined, he’d discretely disappear along the huts at the Great Wall. But he didn’t, he continued living inside his dying. Less than a century after the man who was the original author of the Tao Te Ching died, no one knew precisely when or where he disappeared along the frontier of the Empire. There were arguments over his family name, afterwards he was just called Lao Tzu, Old Man.

Michael Silver Dragon McKain (1939-2010)

Cistern of Atavism

June 22, 2010

The other morning I went out to hand water the garden. It’s a quieting ritual I share with a few birds before the sun comes over the mountain to my east. I noticed the hose didn’t seem to work to draw water from the catchment cistern. After various Laurel and Hardy-like routines of switching hoses, looking in working facets and so on, I climbed a ladder and peered in. The 500 gallon cistern was nearly empty. My body reacted the same way it did years ago when I sat on the curb and saw the car I wrecked, or watched police break through my door, or shook my grandfather’s hand the hot afternoon I got married. A physical sinking flush of realization that I was powerless to change what was happening, and that event was staring into me. Looking in that dark water I felt a deeper unmediated part of me silently shrieking. I felt as if I’d fallen off the ladder and was struggling to run away, but couldn’t…that dream. Be clear, as close as I come to farming is shaking hands with people at the farmer’s markets where I buy vegetables when the weather’s nice. My garden is herbs and ornamentals. I was raised in an industrial city in northern Ohio, not a drought plagued geography. My experiences with cisterns and drought have been limited to tourism, art and literature. So I was more surprised at my reaction than, the actual low cistern. Where did such a deep wild reaction originate from within me, some lost memory, the collective unconscious…was I channeling a maintenance message from the dead owners of this house?

The other morning I went out to hand water the garden. It’s a quieting ritual I share with a few birds before the sun comes over the mountain to my east. I noticed the hose didn’t seem to work to draw water from the catchment cistern. After various Laurel and Hardy-like routines of switching hoses, looking in working facets and so on, I climbed a ladder and peered in. The 500 gallon cistern was nearly empty. My body reacted the same way it did years ago when I sat on the curb and saw the car I wrecked, or watched police break through my door, or shook my grandfather’s hand the hot afternoon I got married. A physical sinking flush of realization that I was powerless to change what was happening, and that event was staring into me. Looking in that dark water I felt a deeper unmediated part of me silently shrieking. I felt as if I’d fallen off the ladder and was struggling to run away, but couldn’t…that dream. Be clear, as close as I come to farming is shaking hands with people at the farmer’s markets where I buy vegetables when the weather’s nice. My garden is herbs and ornamentals. I was raised in an industrial city in northern Ohio, not a drought plagued geography. My experiences with cisterns and drought have been limited to tourism, art and literature. So I was more surprised at my reaction than, the actual low cistern. Where did such a deep wild reaction originate from within me, some lost memory, the collective unconscious…was I channeling a maintenance message from the dead owners of this house?

Sometime in my more academically ambitious past I was researching possible relationships between the contemporaneous Rilke and Jung. I was interested not just in their theories of memory, art and the collective unconscious, but “Blood Memory”. Blood Memory, now primarily restricted to detective novel titles, old Star Trek episodes and confused fringe groups, was a fashionable theory at the turn of the 20th Century. It was a way of knowing without learning or experience. It extrapolated genetics into a primitive cultural feeling of déjà vu by inventing a corpuscular memory bank; it was popular with both artists and racists. It gave credence to unarticulated feelings that seemed too real to be merely transient or random. My Grandparents would have learned about Blood Memory in the same passing way we understand Alzheimer’s disease or deep water drilling. It was Social Darwinism for those who didn’t want to accept or bother to read Darwin.

Eventually my project disintegrated into a pile of manila files, a shelf of pretentious books and unreviewed notes. For me the parts became more valuable than the whole. I traveled to Austria and had a deep, satisfying reading of Rilke in a small cottage with the wind whispering under the door, and spent a couple years in Jungian analysis, and seemed to have moved on. But the value of knowledge doesn’t reside in institutions and mere information, its nature is direct contact and experience. It is the tedious, hand to hand relationship with the world that forms (or deforms) every culture and art piece by piece. Failing to maintain that person by person integration leaves civilizations broken and in ruin. To integrate genuine knowledge of the world requires a marriage, a mutual possession. For the most part that possession is what a university lecture or a museum can only demonstrate in fragments…which in part brings me back to Rilke and Jung and a famous fragment of a statue. In “Archaic Torso of Apollo” Rilke explores a relationship of interiorities between the viewer and the viewed:

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

[Archaic Torso of Apollo, RMR, translated Stephen Mitchell]

He prescribed a kind of reflexive struggle of perception where the viewer encounters an object and is entered by that object. The jarring admonishment Rilke gives at the end of the poem comes neither from the viewer or the object, but from a voice created by possession.

Jung had a similar, if somewhat less lyrical description of possession”… In the state of possession both figures [animus & anima] lose their charm and their values; they retain them only when they are turned away from the world, in the introverted state, when they serve as bridges to the unconscious. “ [Concerning Rebirth C.W.]

The idea that a person can be spiritually or psychically held, enthused, ridden, inspired, taken over by a being or sense other than their conscious mind has been in human parlance since there has been human parlance. And in nearly every form of language possession has been used as a form of preternatural communication.

Possession isn’t at all a foreign notion to our age, not in a world where people strap explosive vests to themselves to fight Holy Wars, the Wall Street Journal publishes articles detailing whether or not members of Sarah Palin’s former congregations spoke in tongues, and people have images of dead loved ones tattooed on themselves. For a great many of us, we are our possessions. Excluding the explosive vests and war, I’m not too critical any of this. I suspect nearly all human beings need to be “possessed” at some times, and some quite frequently. Many of us go deeply out of our way to have that experience. We pray in varieties of ways to varieties of deities, dutifully dance to our favorite songs, do yoga (religious and secular), search for hours to buy rare trash on Ebay, fall in love with strangers, gasp at horror movies, write poems, meditate, keep our dreams in journals, sing in our cars, train for ultra marathons, cry over tele-novellas, obsessively practice musical instruments, dress in period costumes to reenact Civil War battles, and ingest all manner of psychoactive concoctions…all for that perception of both being more than real and genuinely there at the same time. To varying extents we assess the value of our efforts based on the same criteria Rilke and Jung outlined…of being more fully present than we are in the tedium of most of our lives and an other-worldly awareness of simultaneous connection with the past and present and that this connection has resonance in our bodies. Being there.

But there is so seldom an authentic there. It’s a weird adverb; it’s always a relation, and always just there away from us. Both Rilke and Jung seem to agree that to be possessed, to get there to recieve the message requires some courtship, a pilgrimage, a ritual..a great silence. For twenty or thiry years I pursued the mysterious people who built mounds and pyramids all over North America. Since my youth I’ve read and engaged in intuitive preparation, from visiting Mound Builder sites, to sleeping on earthwork serpents, building earthwork sculpture and crawling through terrifying humid tunnels in pyramids constructed to inter much smaller men than me. I didn’t want mere knowledge; I wanted contact.

Not too many summers ago I was standing in the noontime sun estimating how many billion cochineal it would have taken to dye the Placio de los Juguares red, just as my grad student tour guide at Tenochtitlan began presenting her theory of Las Vegas. “It is a simulacrum…designed to look like a Venice, Egypt, or New York, that doesn’t exist except by façade and in the imagination of tourists. It’s a pronoun without a physical antecedent.” Her implication was that tourists were too ignorant to know better, or wanted to co-opt another culture on the cheap. Somehow vacationers and gamblers had no right to experience even a faux physical knowledge of places they hadn’t actually visited. Her thesis was that American architecture had abandoned self possession in favor of the artificial security of commercializing things past.

Apart from the air conditioning, I asked, how that was different from our wandering Mexican ruins imagining the culture that had been there 1,000 years ago?

Unconsciously I had paid an erudite woman to distract my anticipated communion by generating a post PoMo critique of the Las Vegas strip while we were strolling the thousand year old ‘The Avenue of the Dead’. She chattered passionately covering the barely audible trickle of the baths that once fed and cleansed a city of 200,000 sophisticated human beings. She waited in a shaded café while I climbed the legendary Pyramid of the Sun, a structure consecrated over and over in the blood of human sacrifice. The Aztecs visited these ruins, when they visited ruins. It was the home of Quetzacoatl. We could only talk about a fake Vegas.

Neither she nor I could be were where we were, or who we were. She was distracted by a conceptual Las Vegas she found attractive, but not beautiful. I was ignoring the physical fragments of a city I had traveled an exhuasting distance by bus to visit. I wasn’t making a personal connection on any level in the presence of some of the most important monumental art on the continent. I had possession of nothing but a sunburn and a lecture.

And then suddenly one morning I’m looking down the hole of a water tank and I’m stunned. I’ve been siezed in the fangs of Tlaloc, the god of rain. I’m connected like lightning to a dark terrifying world of loss that both Rilke and Jung tell me I should live in and care for like my garden. I’m possessed.

It doesn’t take Rilke, Jung or even a second rate psychic to understand what a 58 year old man sees in the bottom of that well. I was possessed by my own death and it was looking back at me. The dry reality of my limited days and the diminishing resources of my own life were my “borders” and “bursting star”. The message of the warm black water was the same as followed the polished white torso.

Over the next few days when I thought or wrote about the cistern, or Rilke’s broken statue, Jung’s unconscious realm of battling shadows, walking through Tenochitlan or even Venetian canals in Las Vegas. I became nervous and ennerated. I couldn’t read. Mere knowledge was just so much stuff next to seeing my own death. Thinking made me want to brew more tea, drive in to town, check World Cup scores…watch “King Kong” again. Part of me had fallen into that cistern and I couldn’t repossess it.

On a whim I stole a piece of my wife’s water color stock and mindlessly began painting circles with her water colors. First pale painted spheres the size of cherries, surrounded by yellow gold rings, then periwinkle and purple saucer sized loops nestled in the colors of shaded mountain grass, and this encircled by cloudy blotches of blue. It meant something to me, but I had only an inarticulate sense of what it might be. But it brought me a deep physical relief and a faint whispering under my skin.

I believe there is enough water in the cistern for the garden to survive. I believe it will rain soon; I can feel it in my blood.

Shoebox

June 12, 2010

One afternoon when I was adrift in the fourth grade we were told to save shoeboxes. A request so nonacademic I recall the strangeness and mild excitement of it. A shoe box was a commodity in my child’s world, it could store dozens of items, dying birds, mice on loan, left over model car parts, garter snakes, baseball cards. A shoe box was a practice safety deposit box for seven year olds, only surpassed by cigar boxes, the actual safety deposit box of nine year olds. My endless afternoon of faded mimeographs adding fractions, or dividing with remainders was strangely relieved and exotically distracted by this request.

At home I asked for new shoes in hopes of finding the perfect box,

even though it meant an embarrassing visit to Smith’s Boot & Shoe. Smith’s local fame traded on those miniature red cowboy boots so popular in photographs of flash stunned cowbabies and never purchased by my parents. My dear hyper-conscientious parents worried openly about my thinning feet. Like so much of childhood, without preter-parental vigilance any normal detail of life could go arwy and leave one ruined. Dad wore a AAA , and I was expected to de-develop appendages nearing nearing pipe cleaners or bird feet when my growth inevitably surpassed my father. The singular hope I had to avoid podiatric disaster rested in the proper implementation of The Brannock Device. The Brannock was steel and black device not dissimilar to the style of the medical devices already falling out of modernity in doctor’s offices. Ostensibly two simple slides on a calibrated metal tray, to my parent’s mind the Brannock would only be operated by the trained and experienced hands of the city’s oldest shoe clerk, Mr. Smith himself. While waiting for the great man’s attention I was allowed to tarry aimlessly at the fluoroscope x-raying my feet in science fiction green images, but this was a sales diversion for those incapable of utilizing the time-trusted, stinky sock polished tool that remained in its shadowy autoclave beneath a row of chrome legged chairs. I would be properly measured, shoe toes would be squeezed by all, calculations made on my growth, break-in and wear, fashion ensemble options, social engagements discussed for the next year and then another pair of kick-my-ass brown oxfords would appear. After Mr. Smith laced them properly and slapped either side of the leather, I paraded glumly past the unattainable boots, slip-ons and metal clasped rocket shoes. My parent’s chanted in chorus “How Do They Feel? Nevermimd That… How Do They Feel?” My humiliation at the shoe store ended with another pair of shoes exactly like the pair I wore in except for the scuffs. They paid and glowed to other parents and strangers having saved my feet from ruin.“He needs a sturdy shoe. He’d come right out of loafers. Look how hard he is on shoes. Is that as narrow as you have in stock?”

This was the price of a shoe box.

I was never encouraged to read; I was expected to read. Pointlessly, silently, endlessly. I began nearly every book in the child/adolescent section of the Market Street Library. I don’t think I finished many. They were wonderful places to depart into, but quickly they were predictable word list practices or tediously teaching moral lessons. But for my birthday, my mother took me to Strouss Hirshberg Department Store where I was permitted to pick out any episode of the The Adventures of Tom Swift Jr. . It would be mine, no due date, no overdue fines. It had less to do with me as a budding bibliophile, than my mother’s competition with her sister. Her son ,Tommy, had a neat row of Hardy Boys in his bedroom next to the desk that was expected to serve him in solving the mystery of getting to college. My cousin and I were mother shoved forward to resolve imaginary perspectives of moral dilemmas of the future; would the world be one dominated by fraternal detectives or junior scientists? Although I had neither science or math aptitude nor interest, I choose science. At least Tom Swift Jr. promised titles with New! Exciting! Adventure! Adventures, like Mr. Smith’s rocket boots, I would encounter only ocassionally in passing. The cover of Tom Swift Jr. and His Flying Lab ranked highest in my estimation as the kind of book to be carrying in 1958. Although I never flew the lab out of my bedroom, it had cache. It was a “hard” sciencey book, and a coup to have friends observe next to my Classics Illustrated comic books and Revell model of Dracula (one of the few models ever I did complete). To me the entire series of Tom Swift Jr,’s didn’t hold the interest of a Popeye cartoon, yet Tom and I had a few things in common. We were both named after our fathers, had blonde crew cuts and striped tee shirts…after that. He was a rich, industrious inventor called to solve problems all over the world; I had three pairs of shoes, chronic boredom and stacks of unfinished pale blue worksheets hidden all over the bedroom that were always threatening to become problems.

Of course it was a diorama book report. Of course it was on Tom Swift.

Modern dioramas (excluding Bonsai) were first created by Louis Daguerre, a genuine inventor, who also developed the photographic process that bears his name, Daguerreotype. In 1822 he set a London theater proscenium with a series of artistically painted moving sets with diaphanous apertures that gave spectators views of other slowly moving sets overall giving them the dual illusions of perspective and verisimilitude. It was the 3-D, IMAX of its day. It only took a hundred and thirty-some years for Daguerre’s Diorama to devolve into shoe boxes in the hands of fourth graders.

My classmates were busy gluing World War II army men behind bushes

they had swiped from their brother’s train sets. Girls had doll house furniture, tiny chairs, miniature stoves, even shrunken families mired in mucilage. I spent my time creating a private stratosphere on the back of my oxford’s box. A world of crayon blotches and scribbles raced from one corner to the next like meteors avoiding the pasted down cotton wool that had become the non-phonetic parlance for “cloud” in fourth grade. My crayola frescoed box seemed the perfect backdrop to fly a three story atomic powered scientific lab…except I didn’t have a clear conception of what such a vehicle might look like. Rather than look up a corraborating description, I dutifully crumpled page after page of notebook paper trying to invent a flying lab. Finally surrounded by piles of three ring refusee’, I drafted a detailed pencil cartoon, that had it not been a flying lab, might otherwise have been an extraordinarly accurate rendering of shale. What my drawing skills lacked in sophistication were cruelly magnified by my even more limited facility with scissors. The flying shale became even shalier. I glued it midway in the box to present the illusion the great ship was cruising just beneath a thunderhead on its way to foil communist scientists. However, what I had attempted to convey as Tom Swift flying past a cotton cloud, looked more like the business end of a sheep doing its business.

Do I even need to say it was the night before?

Inspired I started on Tom Jr., whom I felt more familar with from his portrait on the binding. Blonde crew cut, toothy smile, yellow and blue striped tee shirt, blue dungarees folding down into legs that I folded down into gluing tabs (sans shoes) and fixed to the front of the box looking to me remarkably like a dimensionalizied illustration on a cover of the book…like a set from television commercial.

I went to bed with a pleasing exhaustion I would come to know more over time,

the weary slumber of a man who has escaped disaster by his own wits. Nothing in Tom Swift or the fourth grade came anywhere close to that pleasure of having prevailed over my own flawed past…I experienced self confidence, then fell unconscious.

Does the obvious need explanation?

Do I need to detail the way a whisper transforms into a titter, and a titter, a laugh, a laugh, laughter? My classmates all assumed I had drawn myself , just without myeverpresent glasses, presiding over two scatological blobs captured in a box of smeared scat. “Tom Swift and the Flying Lab” , I proceeded with my pathetic report just as Tom would have, confident in the ability of the heroic imagination to invent, to outwit sneering villains, and escape disaster at twice the speed of the sound of snickers.

- Shoebox

Being Ill with Romantic Music

October 9, 2009

Being Ill with Romantic Music

Being Ill with Romantic Music

I can’t begin equivocating abstract good from diseases.

Saturday I was in an elevator with a sick woman who coughed and sniffled. I hadn’t slept well the week before and went out that rainy evening to listen to Mendelssohn and Beethoven string quartets. For me that is part of my complicated formula for coming down with a cold or influenza. Romantics put me in a mood for illness. Illness finds me welcoming viral decadence.

Several autumns past I had a lovely toxic bout of fever connected with reading Andre Gide’s “The Immoralist”. For a few weeks in the afternoons I would collapse on the love seat in dreamy naps and wake up physically adrift in my psychic malady. Then I believe it was Richard Strauss and Chet Baker who accompanied my hypnogogic drift. Too many people I loved were dead, or ill, seemed to be hopelessly injured or addicted to something. Mine was a sympathetic disease of indolence, guilt and affectation…and some opportunistic virus. It was a form of intoxication that let me appreciate the willing thrall of Gide’s fiction. It was an especially gorgeous autumn, the afternoons were marked by feckless blue skies, and in the early evening breezes bent north from the Gulf Coast that were still faint with Africa and the decay of low tides.

Now I stagger through Borges’ “Labyrinths” It’s one of my favorite collections of rare dreams and the type of thinking that constructs thoughts both large and enveloping enough for a reader to wander around fragmenting their own life in the Borgesian mirrors. Tedium and twists of language build a tale designed to entrap the reader, and what is Borges if not a diversion in diversions? Like Daedalus himself, Borges creations seem so little concerned with his self expression that he is another near perfect visitor for the sickroom. Along with Borges, Poe’s prolix Auguste Dupin exchange opinions near my night table, advising me about the clues of my experience of captivity and exotic alienation.

So many hours of my life have been lost to the tedious pursuit of money, of what needs to be done (and ignored) in order to earn a living. That world plans our days as its agenda commands, squeezing minutes to task, making time for this meeting, returning calls while driving on the freeway. Even our days off are crushed by lists of duties and pleasures fit together with chronological severity. It’s no wonder sickness is such a lucrative industry in our country, it’s the only place left to be oneself. There is a mysterious liberty in sickness.

Our culture seems obsessed by sicknesses. Sickness requires a higher level of civility and forbearance from those around it. Dressed in our most comfortable pajamas we are permitted to sleep, speak, or be as silent as we wish, doctors and relatives will stop to speak with us, folk cures and patent medicines get passed along as forms of affection. Except for the distraction of discomforts, we are permitted to think whatever our imagination chooses to indulge in—wistful longing, fevered monstrosities, memories, or poetic meditation. That the quality of these considerations may be maudlin and forgettable is secondary to the intensity and novelty of their appearance.

I have flu symptoms. By the latest H1N1 virus television terror alerts I’m encouraged to take my medications at home—expend my sick days for the good of the healthy. I went in to work accomplished a few tasks and left just before noon. I had finished and awakened from my first nap by 2:00. We’re all much more expendable than we would like to believe.

So, if I have to reread the same paragraph several times, it feels as if it were a string quartet passing its theme from movement to movement until it’s resolved. Borges and Poe are seldom direct or well served by speed reading. They seem like suggestions and invitations. Invitations I recieve in a borderland somewhere short of delirium by importune medication where I temporarily reside. In younger, stranger, days it was my desire to build a home there, but now a few days vacation suffice—just as now the mere taste of sweets brings satisfaction. When we are ill in some ways we are spiritually closer to our lost selves.

My dear and beloved friend Billy Parker was diagnosed with AIDS in what seems a century ago, when no one knew about the diagnosis, and treatment was a guess in a cataclysm. He lost everything. I write that as casually as if those three words were no more than two pronouns and an intransitive verb. In the first twenty four hours of his hospitalization for pneumonia, and the subsequent secondary diagnosis, he lost his home, his ability to work, his lovers, and the last years of his youth. But in a strange way he found a second life, not one anyone would have wished for him (or anyone), but a spiritually pitiless and inevitable life. A naked life most of us pretend we’ll never have to live.